The clock is ticking: International medical graduates struggle to find residency programs to practise in Nova Scotia

By Ryan Van Horne, My East Coast Experience, July 13, 2018.

There is a shortage of family doctors in Nova Scotia, but international medical graduates (IMGs) struggle to find opportunities to get licensed here. That’s a painful pill to swallow for IMGs, who have to wait patiently for residency spots while hearing about all the Nova Scotians joining wait lists to get a family doctor.

IMGs are doctors who have completed medical school outside of Canada, but have not yet secured a residency. Some are Canadian citizens who study abroad and then return to Canada hoping to begin their medical careers, and some are newcomers to Canada. A residency is a period of post-graduate medical training during which a resident physician practices under the supervision of a fully qualified physician. Completing a residency is a requirement of licensing for all medical specialties, including family medicine.

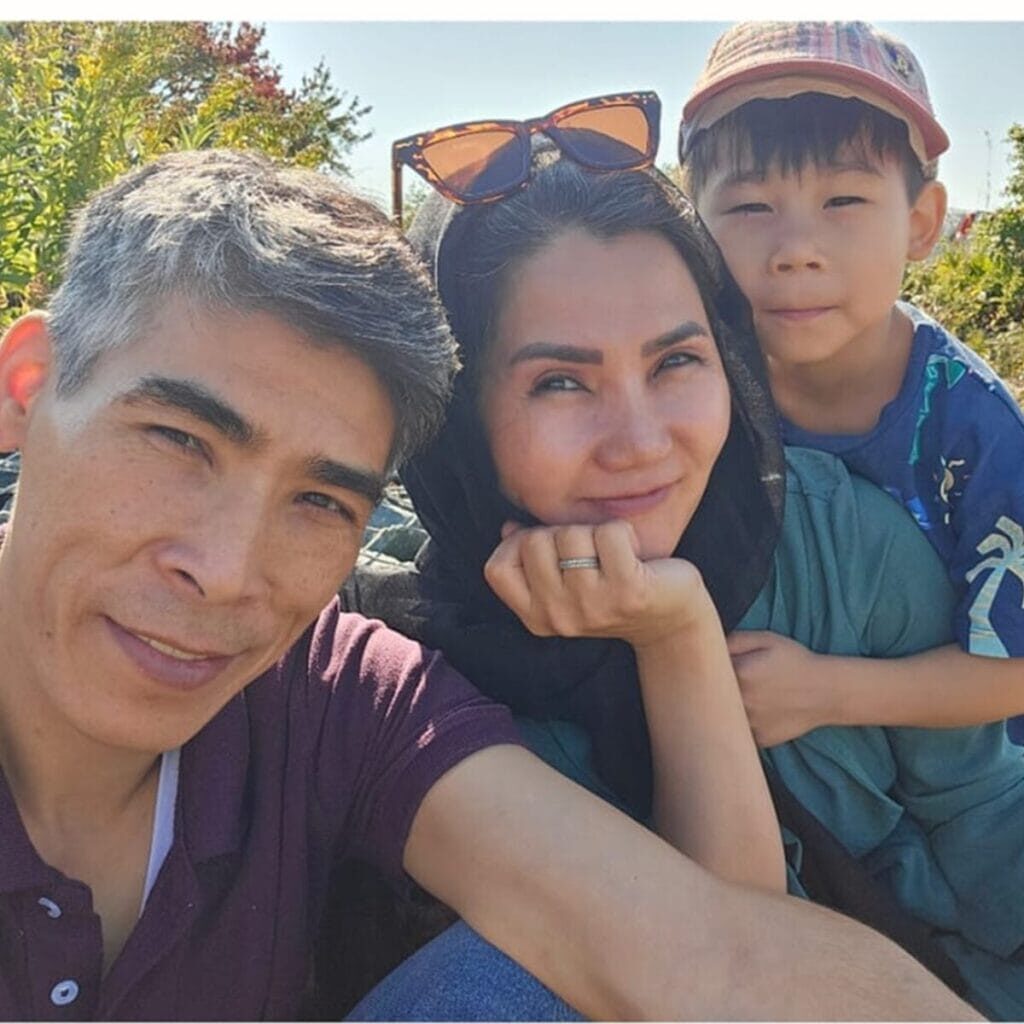

Sara is an IMG. She’s been in Canada since 2014 after moving here from Saint Martin, an island in the Caribbean Sea. Sara is not her real name. It’s a pseudonym she asked My East Coast Experience to use because she feared repercussions for speaking to us about her situation.

“I’ve tried to get work with different doctors,” says Sara. “When I search for jobs, I see numerous rural areas that do not have a family physician, which is what I want to be.” Sara says her sister has lived here since 2014 and still doesn’t have a family doctor. She has bad migraines and can’t get proper care at a walk-in clinic because of a lack of follow-up.

While it’s straightforward for graduates of Canadian medical schools to get a residency spot, a process called “matching”, Sara says it’s much more difficult for IMGs. Jan Sheppard Kutcher, an international labour mobility consultant who works with the Immigrant Settlement Association of Nova Scotia (ISANS), says, “Virtually all Canadian medical graduates match. We’re paying for the Canadian to be trained and, if they don’t have a residency, they can’t work as doctor.”

That makes sense, until you consider the wait lists for people waiting to get a family doctor and you wonder why it’s so difficult for IMGs to get residency positions.

“I’ve interviewed at Dal twice,” Sara said. “After the second interview, I reached out to the university to find out if I could get some feedback for why I haven’t been accepted for training and no feedback has been given.” The only suggestion she’s heard is to take part in more research to make her qualifications “more complete,” but Nova Scotia only offers observer positions, in which a medical school graduate can observe a practicing physician at work.

“As an IMG, that’s the only licence that Nova Scotia will give you,” Sara says. As an observer, she was able to take a medical history and do some physical exams, but nothing more. This inability to get hands-on experience prevents IMGs from getting licenced. “With any sort of medical licensing body, they want to see that you have clinical experience, not just observing.”

Sara has become a regular at ISANS, which helps foreign doctors get their licences. They’ve helped her prepare for exams and supported her during bids to get a residency. Mojha Alia is the manager of the employment and bridging program at ISANS and says IMGs face many difficulties during the long certification process. There are two qualifying exams and an OSCE—an objective structured clinical examination—that IMGs must pass.

“We prepare them for that,” Alia says. ISANS helps by providing study groups, facilitating access to financial support, and language training, though many IMGs don’t need it as their English is already good enough. Alia says the main issue preventing IMGs from getting their medical licence is the available of residency spots. “We need more spots,” Alia adds, admitting it’s not a cheap solution. “It will cost the province a lot of money, but they have to put money into it.” Another problem is the scarcity of practice opportunities for the assessment processes. “I can name at least 10 to 15 who passed all exams but can’t get into a residency,” Alia said.

ISANS is part of a stakeholder working group trying to remove the hurdles that prevent IMGs from practising in Nova Scotia. This group includes the Department of Health and Wellness, the Nova Scotia Health Authority, Dalhousie University, and Doctors Nova Scotia.

Sheppard Kutcher sits on that committee for ISANS and is the co-chair. “Other professions have been able to somehow get it together more easily than medicine,” she says.

Sara points to other provinces in Canada that are doing things that Nova Scotia should try. “In BC for instance, if you find a family physician who is willing to train you and work with you, you can perform clinical procedures on patients.” This doesn’t guarantee that your full licence will be granted, but it’s less restrictive than an observer licence. She also pointed to their residency program, which has a special assessment program for IMGs. “That evaluation is highly considered when you apply, and, if you do well, you’re almost guaranteed a spot for training,” she explains.

In late February, the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness (NSDHW) and the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration (NSOI) announced a new stream to recruit doctors to Nova Scotia. “The new stream is one piece to support a collective effort to recruit physicians,” NSDHW spokesperson Tracy Barron wrote. “NSOI negotiated with the federal government to create this stream. It is an example of how our immigration system can be used strategically to strengthen Nova Scotia’s workforce, and work with our health partners to meet our health care needs.”

The Nova Scotia Health Authority is hoping to attract 12 doctors a year through this program, Barron adds. While any new doctor in a province with a wait list for family doctors is a good thing, it doesn’t address the backlog of IMGs who are already here and have the education—but little to no opportunity to complete a residency.

Sara is one of the people left in the cold by that announcement. “I don’t think it’s fair, because it’s opening it up for people outside of Canada to come in and obtain jobs,” she said. “There are already people who have immigrated here who are doctors who are trying to get licensed. Why not help them?”

Sheppard Kutcher says the announcement is a good example of how the different levels and departments of government can work together, but it was essentially trying to “bypass the barrier” that exists for IMGs seeking to get their licences, rather than removing it. “There’s a significant group of IMGs who are already here,” she said. “Rather than deal with them, they’re going to recruit physicians from the US, the UK, and Australia and bring them in because they won’t face the same kind of barriers because their training is recognized.”

Sara says the doctor recruitment program announced in February makes it easier for doctors who are already licensed to come to Nova Scotia, but it doesn’t provide more opportunities for IMGs looking for training to finalize their qualifications. “The onus is on the health authority to create a stream to licence physicians and not on Immigration to recruit more doctors,” she said during her first interview with My East Coast Experience in February.

So, who is responsible for fixing the problem?

“No one person owns it,” says Kevin Chapman, the director of partnerships and finance for Doctors Nova Scotia. “It requires a collaborative solution. It’s not that anybody has deliberately stacked the deck against IMGs. It’s a gap in the system that we need to recognize and really need to try and address.”

Sara thinks it’s as simple as recruiting more teachers. “They do not have enough teachers,” she says. “I don’t think it’s a matter of a lack of funding, either. They have money to pay for physicians in rural areas. They need to provide an incentive to train the doctors.”

One of the biggest challenges, Sheppard Kutcher said in February, is that there is no way by which IMGs can demonstrate that they are practice ready. There used to be a Clinician Assessment for Practice Program (CAPP), but it was scrapped for financial reasons.

Chapman says his organization has been consistently calling for a replacement for the CAPP. One thing that will have to be fixed is providing more opportunities for doctors working on defined licences to actually study. Defined licences are sometimes issued to physicians who have not completed all of the qualifications necessary for full medical licensure. Finding time and opportunities to study can be difficult for doctors working in rural areas, especially specialists. “It’s a huge issue,” says Chapman. “These folks have to cobble together time and supports and try to write the test to achieve full licensure… It’s most assuredly next to impossible.”

In early April, the NSDHW approved a practice-ready assessment program that had been developed under the guidance of Grayson Fulmer, the Nova Scotia Health Authority’s senior director of medical affairs. “We had a project team develop a proposal for what practice-ready assessment (PRA) would look like for Nova Scotia,” explains Fulmer. The new PRA program will assess internationally trained family doctors looking to work in Nova Scotia and will accept 10 candidates every year. The first group of candidates is expected to begin their three-month assessments at Dalhousie Family Medicine in early 2019.

“This program will see new family doctors, every year, providing more access to primary care in Nova Scotia,” says Health and Wellness Minister Randy Delorey. “The Practice Ready Assessment Program will be another important recruiting tool, much like our existing residency and financial incentive programs.”

Successful candidates will get a conditional licence to work in underserved areas, including Halifax, Dartmouth, Cape Breton, the Annapolis Valley, and northern Nova Scotia. Dalhousie will oversee the program, which will be mirrored against Medical Council of Canada standards for practice-ready assessment. The program draws a lot on the lessons Nova Scotia learned from the CAPP. It is expected that the first group of candidates will be ready to practice in Nova Scotia by the fall of 2019.

Sara is cautiously optimistic about the program. “This is definitely a step in the right direction,” she says, even though this program won’t affect her because she hasn’t done her residency. “They still need to expand the spots to train other doctors,” she said. And, until she hears what the eligibility requirements are, and how it plays out, she won’t know how effective it will be and will reserve judgment.

Sheppard Kutcher is concerned about IMGs who have been here for several years. “The clock is ticking for IMGs who are already in the province, because once they are ‘out of practice’ for five years, their options become extremely limited, almost non-existent,” she said.

While it’s good to see opportunities available for family physicians, Sheppard Kutcher says the next step is to create them for specialists. “Other healthcare professions, such as pharmacy, nursing, and dentistry—professions that also have serious public-protection mandates—have pathways to licensure which are highly rigorous, but enable any internationally trained individual to challenge their knowledge, skills, and competencies against Canadian standards in that profession, regardless of labour market demand,” she said. “Medicine needs to catch up.”

Share this